We arrived in New Delhi in the last week of August, 1985. Mr. Shaw, the secretary of the National Assembly of India, welcomed us warmly at the airport and took us to a guest house owned by a Punjabi lady who rented it exclusively to foreigners. It was a well-maintained two-bedroom annex with a washing machine close to her main house. We were all so tired that we went to bed and did not open our eyes for ten hours. Our hostess served us an excellent breakfast. We went to a nearby 5-star hotel for other meals.

Two days later Mr. Sahba, the architect of the House of Worship, came to the guest house to greet and welcome us. He gave us some suggestions as to where we could find affordable housing and gave the names of neighborhood schools. He advised me to have my office at the temple site instead of at the Bahá’í House which was quite a distance away, so that we could be closer.

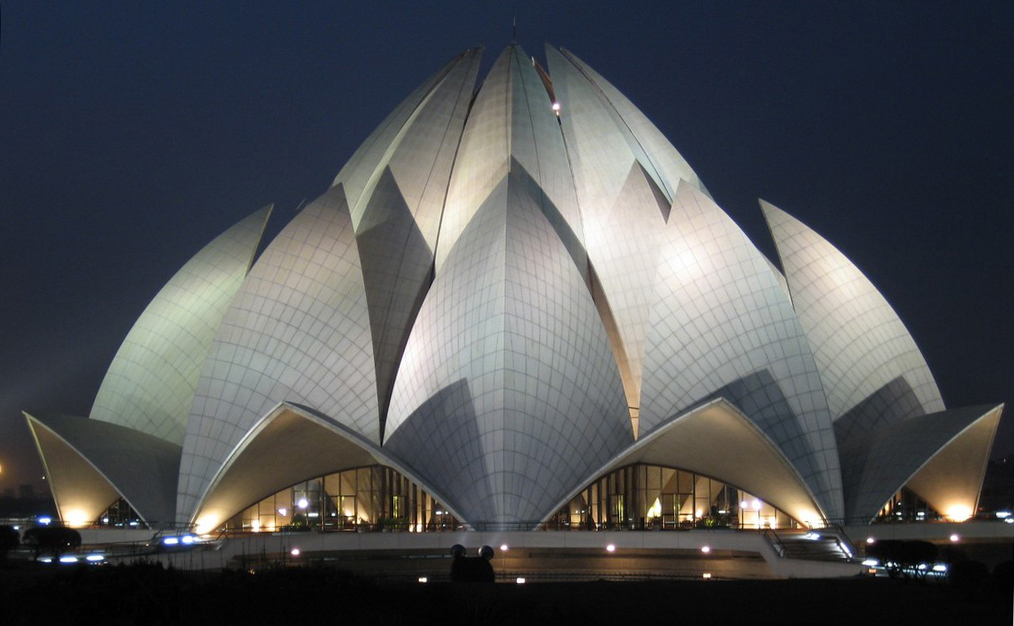

The next day I went to the construction site to meet Mr. Sahba. There was a row of temporary mobile wooden structures serving as offices from which the work was directed. In his office I saw for the first time an impressive plastic model of the temple. I also saw poster-size blueprints hanging on the wall and spread over a large table. After describing the salient features of the model, he dismantled it and put it back together so that I can see how the parts and pieces were fitted to make the edifice.

He then gave a rundown on the progress made during the past nine years. I inquired how he managed to get such high quality work from the Indian labor force. He showed me a blueprint of one sections of the structure that was being built that week. It displayed in minutest detail the rigid specifications are to be uncompromisingly followed. He took me to a closet where over five hundred such blueprints were stored. They were generated in 1975 in collaboration with an architectural firm in England which had the advanced software needed to translate the architect’s vision into reality. He also pointed out that it is common practice to have an architect design a structure and then employ separately a project manager for its construction. Very often the project managers compromise on the mandated specifications for want of time or funds. But in this case, Mr. Sahba himself was not only the architect but also the project manager, thus producing the quality envisaged. He had two experienced Persian Architects cum civil engineers and a sizable crew of volunteers from Persia who closely monitored and scrutinized the work of the Indian subcontractors during and after completion of each operation. A renowned Indian consulting and construction firm, Larson and Tubro was the subcontractor. I very soon recognized Mr. Sahba to be a genius, highly dedicated to the Faith, extremely intelligent, and a thorough professional. He was a task master with a “zero tolerance” for sloppy performance.

It was expensive to live in the guest house, so we moved to Bahá’í House in Canning Road near the center of town. During the ten days that we stayed in the guest house, the landlady’s dog, a Tibetan Terrier, gave birth to several puppies. Shaku and Vivek became very fond of these puppies, and the landlady gave one of the cutest puppies to them in memory of our stay with her. We planned to pick up the puppy when we had moved into a house of our own, which we thought would be in a short time.

Kids’ Schooling

All schools in India are private institutions run by Missionaries or other philanthropic organizations. One Mr. Narrinder, the son-in-law of Mr. Shah, was to be our guide in finding a house and appropriate schools. Unlike in the USA, the school year in India begins in April. This meant that our kids would have to enter the school in the middle of the academic year if admission is available.

First we went to the British School where Mr. Sahba’s two sons were studying. The principal said that he has no way of admitting any student in the middle of the year and gave me an application for admitting Vivek the following year, that is, in April 1986. I then took Vivek to the well-known Don Bosco Boys High School, run by Catholic missionaries, where the principal hesitated to admit him in the middle of the year. The fourth-grade teacher administered a short entrance test in English and Arithmetic and found Vivek to be intelligent and ready. While Vivek was being tested, the principal, who was a Catholic priest wearing the attire, said that Vivek’s admission was conditional upon my paying the customary amount of RS. 5000 ($400). Friends had cautioned me about such a practice which, in the culture, is tantamount to “under the table” money. I was shocked, but soon recovered and calmly said, “You and I both are serving the same Lord in different ways. I am not encouraged by this practice.” His tone became somewhat apologetic and he waived me from paying such a donation.

It took some time and research to find a place for Shaku. As expected we had problems in finding a school that would accommodate Shaku’s needs. The American Embassy School said that they could set up a program for her but at the cost of Rs. 5000 per month. This we could not afford. Finally we got her admitted into a girls School, Junior & Tiny Tots, which was designed to accommodate children of foreign nationals living in Delhi with a program to strengthen their English language communication and social kills. We told the principal of Shaku’s developmental challenges, but she still gave her admission. Their bus picked her up two blocks from our house.

I was happy to have two of my relatives living in Delhi at that time. One was my teenage buddy and school mate, Vidhyanathan, with his family and the other was Raghuraman, my uncle’s son. Also in the community was a French Canadian Bahá’í, Mr. Michael Campau, serving at the Canadian Embassy in New Delhi. Our dog Todo grew up into a lovable pet and kept entertaining the kids.

House Hunting and Settling

We spent four frustrating weeks shopping around for a suitable house without any result. Finally Narrinder, through a real estate agent, located a three-bedroom single-storey house that was in the final stages of construction. Nana and I went and saw the house which had a good floor plan with a reasonably sized kitchen and large dining room. This was the best house we had seen so far. We decided to rent it, though the rent was more than we had expected to pay. The owner, who lived in Hyderabad, promised to make it ready for occupation in three weeks.

Now that our address in New Delhi was fixed, we applied for telephone and liquid petroleum gas cylinders for cooking. These things take their own time to come, unless you pay under-the-table cash. I went with Nana to the Gas Commission office directly as they give preference to foreigners. The commissioner said it would take a month, to which Nana retorted, “I want to cook today, not next month!” With the kind help of my cousin, Raghu Raman, who was the Director of Quality Control and Productivity in the central government office we got both the telephone connections the day after we moved in the house. Fortunately our shipment from Vista, California arrived on time.

It took almost two months after we arrived in Delhi to have the house set up with furniture and drapes for the dining room and living room. Nana as usual transformed this house into a lively home. It would have taken us about two weeks to move and settle into a new city in the USA, but it took almost three months in Delhi. For the first few months Nana did all the house work and later had a woman domestic house keeper, Mathura, for cooking and household chores. We missed having Nanda Bhai of Panchgani and even thought of bringing her to Delhi to help Nana.

During this period I spent half my day settling the home and the other half setting up my office at the Temple site. I had to start from scratch. I was given a desk, a chair, and a new filing cabinet in a room not too far from Mr. Sahba’s. I also had at my disposal an Ambassador four-door car. This was the only car at the temple site besides Mr. Sahba’s personal automobile. The arrangement was that this car should be shared during the day with Mr. Sheriar Nooreyezdan. He was the proposed Maintenance Director of the Temple after its inauguration. He was then serving as the right-hand man to Mr. Sahba for materials purchase. We were surprisingly and accidentally lucky in locating a trustworthy and safe driver, Shankar. He spoke Bengali which I could also speak fluently.

The first order of business was to have telephone connections. This took over three weeks in spite of the fact that the Temple Site office of Mr. Sahba had prior authorization for additional lines. In those days there were copying machines, but there were no fax machines or PCs and the offices had only manual typewriters. Fortunately I had brought my portable electric typewriter. The secretaries took shorthand notes and typed the letters. I got my office stationary and business cards printed by a shop owned and operated by a young man who had been well trained in Singapore. He was very reliable and produced quality work. I also prepared information folders containing basic information about the Faith, the significance of Houses of Worship, pictures of the model of the Indian House of Worship, and announcing the coming of the Dedication ceremony.

Soon after my arrival, Mr. Sahba convened the first meeting of the Dedication Committee appointed by the Universal House which included, besides Mr. Sahba and myself, Mr. Sheriar Nooreyezdan, Dr. Davies, and Mr. Mohan Munje, a member of the National Spiritual Assembly of the Bahá’ís of India. Dr. Davies, a Bahá’í from the USA, was stationed in New Delhi with UNICEF in their Public Health division. We had two consecutive meetings doing brainstorming about the tasks before the committee and getting to know each other. We also established a procedure for getting and managing the funds needed for the dedication committee’s work, which was to come from Mr. Sahba’s budget for the Temple construction project. Narrinder, who was the office manager in the National Assembly’s finance section, was asked to create a separate account for the dedication expenses. A limit of how much money I can draw at my discretion was agreed upon, beyond which the Committee’s approval was needed. I was allowed to recruit or consult with as many individuals I want provided they are providing the services pro bono. From the data we had on the dedication experiences of previous temples, we estimated a minimum of six to seven thousand Bahá’ís to attend the dedication ceremony, a third of them from India itself.

A Plan for Action

To begin with I generated a long list of the tasks to be accomplished and categorized them under several phases. Even though we were not sure as to when the dedication would take place, a rough and preliminary PERT chart was developed. I researched and compiled the local resources. With the help of the Ministry of Tourism and the Mayor’s office, I gathered information on foreign embassies, travel agents, conference halls, stadiums, international hotels, youth hostels, dormitories, and YMCAs. I pinned the essential locations on a poster-size map of New Delhi. This took almost a month to accomplish. If New Delhi had a Chamber of Commerce, as we have in the USA, all of this information could have been obtained just in one visit.

In early October of 1985 the committee and the NSA of India consulted on the best time of the year to hold the dedication that is convenient for both the Indian and foreign Bahá’ís. After examining several dates it was decided to have it during the Christmas holidays between December 23rd and 27th of 1986. The House Of Justice approved the dates. Mr. Sahba had a 24-hour work schedule with three shifts for the finishing the edifice, and he was positive that the Temple would be ready by that time. That meant we had fourteen months. I refined my PERT chart, inserting the deadline dates for each of the tasks to be accomplished.

One day in October we got a most welcome note from Nana’s aunt Paulette in Montreal, saying that she had retired that she was making travel plans to come to visit us in New Delhi. But a week after that, we got a shocking telegram that aunt Paulette had passed away of a heart attack. She had the tickets and other documents ready and was so excited about the travel. I was convinced that Nana should go to Montreal to attend the funeral to bring a closure. After some initial hesitation Nana took the next available flight to Montreal.

The first Bahá’í from the West to visit me was Mr. Tom Price, a well-known music and choir director who stopped by for a few days on his way from the USA to Sydney, Australia. He had a degree in music from a university in Sydney, where he also lived at that time. He was keen to offer his voluntary services to take charge of recruiting and bringing a Western choir group for the dedication. He had provided similar service to several Bahá’í conferences, and this offer was warmly accepted by the committee.

Tom also suggested that we should consider Qantas, an Australian airline, as the official carrier of the Bahá’ís from their countries at a substantially lower rate. He said that the chief of their sales division was a dear friend of the Bahá’ís in Sydney. He could arrange a meeting with him the next time he comes to Mumbai. Since the committee wanted to encourage Indian businessmen as much as possible, we had earlier decided on Air India as a possible official career and kept Qantas as a backup.

In less than three weeks Tom was back in New Delhi to meet the committee as he had been successful in scheduling a meeting in Mumbai with the Qantas chief of sales. Mr. Sahba and I traveled with Tom and we also set up an appointment with the Sales Director of Air India. The idea was to compare the offers from two carriers. Both the companies were eager to be designated as official carriers, but said it would be impossible since the dedication was at the end of December, their busiest money making season. This, even though we assured them of 3500 passengers from outside India.

During his stay in New Delhi, Tom noticed that I did not have an experienced English-speaking secretary. He suggested that he would approach his mother, Ms. Lorraine Price, and inquire if she will be interested in offering a volunteer year of service to serve as my secretary. She had secretarial experience working with real estate agents and also for the National Assembly of the Bahá’ís of Australia. Ms. Price arrived in late October which was a major relief for me. Nana found her to be a warm and very personable lady. The chemistry between them was so compatible that she stayed with us for six months. Nana had a good companion and our kids loved her.

One day in December, one Mr. Charles Nolley, who was working at the Bahá’í National Office of the US community, came to see me saying that he was designated by the US National Assembly to be the person to film the entire dedication ceremony and the conference that was to be held in connection with that event. He met with the committee his services were gladly approved.

Among the other visitors that year was my dear old Calcutta friend Goswami of Phillips. He was totally taken aback when he learned what I was doing in Delhi and that I had left my career in the USA. He had an opportunity to meet Mr. Sahba and they consulted on the possibility of Phillips being a part of the consortium that would plan the night illumination of the Temple.

My brother Srinivasan came on a business trip to Delhi and stayed with us during the Christmas holidays. Nana arranged an excellent welcome party for him, assisted by our maid Mathura and another cook. The house was spacious enough, and more than twenty guests were present.

In December I was very fortunate to get a letter from an Australian Bahá’í, Mr. Tony Thomson, offering one year of voluntary service to the dedication committee. He was a retired principal in one of the Melbourne schools. He arrived in Delhi in early January and rented a bachelor apartment not to far from our place. Besides being my right-hand man, Tony became a close friend. In fact, he came along on a family weekend trip by train to Gwalior to visit with Steve and Sherm Waite where they were running a Bahá’í school. We had known the Waites in Amherst. Todo traveled well.

With the invaluable assistance of these two Australians, Lorraine and Tony, I was able to accomplish things at a much faster rate. Later in the next few months I invited two US Bahá’ís, Mr. Tony Pelee from Chicago and Ms. Eileen Norman from California, to come as consultants at two different intervals. Both of them, I knew, were experienced conference planners since I had worked with Tony in the National Assembly in Hawaii and with Eileen in the International Goals Committee during my Amherst days. Luckily they each were able to come on a voluntary basis, Tony for two weeks and Eileen for a month. This was a real shot in the arm as they gave valuable suggestions to help me accomplish the tasks ahead of me.

The First Phase

During the four month period between December and March of 86 the following tasks were completed and clearing every decision through the Dedication Committee. Whenever it was essential, either Mr. Sahba or Mr. Shaw and some times both of them accompanied me in my meeting and negotiating the contracts with the parties. Needless to mention, Mr. Tony Thomson, my right-hand man, was always with me. Ms. Lorraine Price, who could compose a draft letter merely from the points I give her to be conveyed, was an incredible asset in this process.

* Selected two Travel Agents, (Sita Travels and Travel Corporation of India) and negotiated a contract stating clearly their individual role in serving the participants. This contract included arranging and scheduling bus transportation (if available in deluxe buses) between the Temple site, conference stadium and the different hotels. They will also give us a written itinerary and rates for pre- and post-conference tours of India.

* Confirmed the Indira Gandhi Arena for the conference. This was the site of the 1982 Asian Games.

* Secured the Velodrome near the Arena for conducting children’s classes and rooms for the book stores.

* Negotiated a contract with each of the major hotels and other selected places that will be housing the participants. Negotiated the rates they will be charging. There were 35 lodging places with prices ranging from $8 to $40 per night.

* Contracted the services of Pandit Ravi Shankar as the composer, producer, and director of Indian choir music to accompany the lyrics selected from the Bahá’í writings. He had a minimum of thirty members in his team for whom the committee provided room and board for ten days before the dedication ceremony. Ravi Shankar was not happy to learn that no musical instruments were to be played in the Temple according to the Bahá’í writings.

During this period I spent late hours at work and saw my family only during the weekends and when I took them out to eat. The Lodhi Hotel, which served South Indian meals and snacks like rice/lentil pancakes (called onion-rava-masala dosa), was our favorite. Vivek brought home loads of home work every day. There was no TV or other distraction, and he completed his fourth grade with good marks. His Don Bosco experience was very positive though he had over forty students in his class. It was in this school where he learned to study and work for over several uninterrupted hours. In April of 1986 Vivek was admitted to the fifth grade in the British School where he was happier. Shaku stayed in the same school, as her experiences were also positive due to a caring art teacher.

By the middle of March we had all the information needed to produce the information and registration booklet to be sent to the Bahá’í world. The brochure was designed and approved by the committee and then the National Assembly. I made sure that adequate space was given in the registration forms. My experience had shown that those who design forms leave very little space to write, and let many questions go unanswered. Only a third of the Bahá’í population had English as their native tongue, and I wanted the information in the brochure to be easily understandable to a eighth-grade student. The brochure went to press after being field-tested for clarity.

The Bahá’í Publishing Trust of India printed 8000 brochures. They did a superb job, and in four weeks had them packed in batches of twenty-five. The staff at the Publishing Trust mailed the information packets to all the National Assemblies across the Bahá’í world by registered air mail to guarantee their delivery by the middle of April, in time for the National Conventions. The registration deadline was August 31, 1986 which gave adequate time for the Bahá’ís to make visa and travel arrangements. This would also enable the committee to make further post-registration arrangements for the 6000 or so registrants from abroad. It was then the end of April and the first phase of the project was complete.

The Second Phase

The deadline dates for the subsequent phases of the project were revised. This time Mr. Michel Campau of the Canadian Embassy produced for us a computerized PERT chart. Mr. Shahram, a Persian Bahá’í fluent in both English and Hindi, was working with Mr. Shah in the Bahá’í National Office. He was transferred to the dedication project, and his initial task was to research and identify artisans for producing high-quality art and craft items to be sold as souvenirs and gifts at the dedication. Mr. Shahram was also to get information about local vendors for supplying conference bags and badges for all the participants. He was very energetic and willing person — a welcome addition to our staff.

One day in June Ms. Jena Sorabji, Counselor Sorabji as she is known, came to our committee meeting with a sample of a conference bag artistically crafted out of straw with a logo of the House of Worship, tastefully crafted at Barli Development Institute for Rural Women, Indore. If we approve the material and the design of the bag, the women at Indore Institute would supply, at minimal cost, the needed number of bags. We liked the idea and the design and told her that the number may be ten thousand. Counselor Sorabji said that they have to start working right away that month so as to have them ready by the second week of December which was six months away. In fact, after incorporating the changes in the design suggested by Mr. Sahba they delivered the product proudly on time.

Next on the Committee’s agenda was to come up with an efficient plan of processing applications from the registrant. A punch-card system as used by the utility companies was one suggestion. That was a labor-intensive, outmoded system. I wanted computers to do the task, which would make it easier to retrieve the specific info we and the travel agents need on any registrant. In the meantime, registration applications were piling up day by day. I was able to locate two young and energetic software consultants who were working for Wipro, an industrial firm in Bangalore. They gave a bid after looking at the job to be done. The idea of using their services was put on hold till the application dead line was reached.

The hot New Delhi summer arrived well ahead of time that year, but temperatures some times more than 50C. did not put any dent in the progress of the Temple construction. There was no air conditioning in our house except for a “desert cooler” in the living room. Nana could see that I was getting exhausted easily and slowly showing signs of burn out due to the stress of my work. The months of June and July were the worst and I feared I may have a nervous breakdown if I was not serious about my health and mental condition. This was noticeable to Lorraine, Nana, Tony, and others. I realized for the first time that I was beginning to doubt my own capacities. I felt certain that if this debilitating condition was not corrected immediately the progress of the work would be damaged beyond repair and I would be of no use to either the committee or my family. Relying on God, I prayed with all my heart and soul for guidance.

I wrote a letter to the Universal House of Justice in Israel, expressing my lack of talent, my mental frailty, and my timid management of the job. I knew that my real work as Coordinator of House of Worship Activities would truly commence after the dedication. I expressed my true doubts at that time as to whether or not I could be useful in serving on the committee. And I stressed that above all I wanted the dedication Ceremony to be a very successful event. I requested their guidance and prayers. I prayed for firmness in the Covenant. I was detached and willing to abide by what ever guidance I got.

Two days after I mailed the letter, Counselor Sorabji and Mr. Shaw invited me to come for a meeting. When we arrived I saw Mr. Sahba was also there. Mrs. Sorabji began by expressing their concern about the stress I was experiencing in my work. They gave me the option of being relieved of the assignment if I wanted to. Though Mr. Sahba did not say much, intuitively I felt certain that he was concerned that the dedication ceremony of such a historical edifice — his brain child, into which he has put his heart and soul — would be a disaster. I told them I had written to the House Of Justice and that I was waiting for their guidance, by which I would abide. The three were surprised that I had already written the Haifa on the situation. At his request I gave a copy of the letter to Mr. Shaw the next day, who sent it by Telex to Haifa. This, he said, was to get their guidance with out any delay. Overseas letters in those days took a minimum of ten days to reach their destination.

With in a week, the National Assembly of India got a Telex from Haifa approving my resignation and giving me the option of resettling in any country I wish. They also directed the Assembly to give the family all the assistance needed. Two days later, during a dedication committee meeting in which I was reporting what was happening, we got a call from Mr. Glenford Mitchell, a member of the House of Justice. He relayed to me the same message sent earlier by Telex and conveyed that I would continue receiving my stipend for six months or until I got a job, whichever comes earlier. I thanked him for the call, but could not speak to him more to consult on my future plans as I was surrounded by other members of the committee. Then I met with the National Assembly of India and strongly recommended that retired Col. Tony Pelee or Ms. Eileen Norman take over my position as quickly as possible. I felt they possessed the experience, style, and temperament needed to do the job.

The Last Phase — A Turning Point

Within three weeks Tony and Charlotte Pelle arrived in Delhi. I felt that I had a moral obligation to see the committee’s work finished whether or not I was a member of the committee. After consulting with Nana, I offered my services to the National Assembly of India to serve as a volunteer to assist Tony Pelle so that he can take up the work from where I left without any lag in the schedule. This was gladly accepted as at that time I was the only one besides Tony Thompson who had all the information and channels to jump-start the work. I felt relieved of the burden of responsibility. In my interest to land this boat safely, I became a happy oarsman instead of the coxswain. This was also a good move in that we would be able to stay in India until the children finished their school year in April of 1987.

Tony’s coming was a major turning point in the progress of the committee’s work. I found Tony to be charismatic, and in his style he was somewhere between a drill sergeant and a cheer leader. The key to his success was delegation. His first order of business was to have the computer system set up at the Bahá’í House to process the conference registrations. He was also able to delegate the responsibility of registering and hosting the Bahá’ís from India to Mr. Gandhi, a knowledgeable member of the National Assembly. Mr. Gandhi was an active politician before he became a Bahá’í and he knew the ins and outs of such an assignment. Mr. Gandhi and Tony commissioned Indian Army contractors to erect a tent camp to accommodate the Bahá’ís from the rural villages. It was an impressive camp with weather proof cabins, running water, portable toilets, plus kitchens and dining rooms for about one thousand residents.

Tony put me in charge of making a list of VIPs to be invited to the dedication ceremony in consultation with Mr. Shaw and Counselor Sorabji, and then designing and printing an attractive invitation card for the VIPs. This would involve the foreign diplomats, Indian government leaders, people of prominence, and the heads of the various religious denominations in India including the Vatican representative in Delhi. Tony himself spearheaded the personal invitation to the President and Prime Minister Of India, the Russian and American ambassadors and others, with me accompanying him. The President and the Prime Minister of India sent their representatives and we got a good number of responses to the RSVPs from others. Thank-you notes were sent to the respondents with special VIP dedication badges. I sent invitations to my parents, my brother Srinivasan, and also my two relatives who were living in Delhi. Only Vidhyanathan and his wife came to the ceremony.

I was also delegated to plan and get the resources for the children’s program. There were over four hundred children registered. With my experience at the Kansas City Bahá’í Conference in 1974, plus the invaluable help of Mrs. Sherm Waite of the Gwalior School and a sizable number of volunteers from abroad and from the New Era School in Panchgani, we pulled it through. We had magicians, yoga demonstrators, Indian classical dancers, mahouts with their elephant shows, and puppet dancing in the children’s program.

In early November the committee’s offices were transferred to the Bahá’í House as the Temple grounds were to be cleared of the enormous amount of construction debris before landscaping. By early December the House of Worship was completed and they made seating arrangements for about 4000 which included the 1200 fixed seats.

Nana joined the registration crew working closely with Mrs. Lorraine Price in typing the identification badges. Nana was also a member of the Western Choir commissioned by Tom Price. Mrs. Eileen Norman arrived early enough in December to work with program committee and be the stage manager for the dedication ceremony at the Temple and the conference.

A week before the dedication day we had a dress rehearsal of the whole program including the choir music. The protocol for seating the VIPs was established and about three hundred seats in the center aisle were cordoned off and numbered for VIPs. Specific instructions were given to the volunteers who handled this section.

By the first week of December every thing fell into place and we had an inspiring dedication ceremony and a marvelous conference with over eight thousand Bahá’ís attending. We had to hold two separate dedication ceremonies, one in the morning and one in the afternoon. It was a wonderful and deep emotional experience to see the Bahá’ís of every religion, race, skin color, and ethnic origin dressed in their native costumes seated in that circular auditorium, all confirming the oneness of mankind and turning their hearts to the Almighty.

Post Dedication Saga

We were planning to leave India after the children had finished their school year, but in late January 1987 I got a call from one Dr. Geoffrey Bishop, the principal of an international school in Mussoorie, inquiring whether I would be interested in a position as vice principal. Geof was a Bahá’í from England who had been recruited as principal of the school established by a multimillionaire Mr. Raval, who had a roaring business in Kenya. This was a residential school for girls whose parents had emigrated out of India. Nana and I went to Mussoorie to check out the school and the town while the children stayed with my cousin, Vaidhyanathan. The school was a five star construction with spacious classrooms and modern kitchen and dormitories. It was architecturally very pleasing. Mr. Raval was keen on making the school an official International School following the Geneva International Schools Association’s curricula.

After negotiating the offer in terms of the salary and perks, we all moved to Mussoorie (including Todo) even though no official contract was signed. I had complete faith in the principal’s promise and commitment to get the official contract on the first day of school. Shaku was comfortable residing in the dormitory and Vivek went to a boys school, as Raval’s school was only for girls. But Nana had reservations about Mr. Raval and felt very uncomfortable and nervous when he was around.

We spent three months during which, though the salary was coming as promised, there was no written contract in spite of several reminders. One day a teacher brought me an advertisement in the newspaper for a vice principal’s position at the School. Mr. Raval did not consult or inform Geoffrey, the principal, of his intention. We were shocked and it was professionally embarrassing for me. We said goodbye to the school and informed the National Assembly of India and the Universal House of Justice as to what had transpired. The National Assembly got a message from the House of Justice to defray the cost of relocation to the USA. Nana wanted to go back to Canada, as were all Canadian citizens. It was also suggested by Mr. Campau of the Canadian Embassy to go to Ottawa, but we went back to California instead as I had more professional contacts there.

We also learned as we were leaving India that when Geof returning to Mussoorie from his vacation in England, he was detained at the airport for three days on visa issues. Mr. Raval had a lot of political connections and he had realized that we were both Bahá’ís. Thus came the end of Goff also as the principal of the school.

Before leaving India I visited my parents in Rourkela and only Vivek came with me as Nana and Shaku opted to stay in Calcutta with my friend, Mr. Bharat Bhushan Bhatia. At the end of June 1987 we flew back to Los Angeles taking Todo with us. The carrier, Japan Airlines, made Todo’s air travel very comfortable even though he was in the cargo section.